ROBODOC® System

Min Yang Jung | 31 Dec 2016When I decided to work on the software system safety as my PhD thesis topic, it didn’t take long before I realized safety in the medical robotics domain had not yet been formulated as a well-defined research problem. Although virtually all papers in the medical robotics domain mention (the importance of) safety, it has been mostly considered in the application- or system-specific context, rather than as a system property that requires systematic approaches.

So I spent quite a bit of time – almost a year – for literature review in various areas such as software engineering, component-based software engineering, system safety engineering, safety- and mission-critical application domains, dependable computing domain, and so on. Two major findings (I’ll write another post that overviews those related domains later):

- Within medical robotics, there is a lack of prior work that specifically focus on the safety of medical robots.

- Outside medical robotics, Safety has been already recognized as one of crucial system properties and as such there is a substantial body of work around it.

This was a good news to me in that I had room for contributions, but at the same time was not a good news because there were not much of prior work that I could refer to for my research.

Fortunately, there was one medical robot system, of which many aspects are relatively well documented and published in the academic medical robotics literature: The ROBODOC® system system, an orthopedic surgical robot system. Starting from its history, the topics they cover include user-driven system design requirements, an overall system architecture, design rationale, safety design principles, and some of engineering details. Even though most of these papers were published in the 90’s, I personally learned a lot from those articles, which later became my primary resource for my own research on safety, including my PhD dissertation. So I thought a list of those papers with the history of the ROBODOC system may be useful for those who are curious about ROBODOC, who are interested in safety in general, or who are (about to) working on safety as a research topic. The list of the literature that I reviewed includes Taylor et al. (1990, 1991, 1994, 1996), Kazanzides et al. (1992, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1999), Mittelstadt et al. (1993, 1996), and Cain et al. (1993). For a complete list, please refer to the Reference section at the bottom of this article.

DISCLAIMER: This article is an excerpt of my PhD dissertation (Section 6.2.1), which was proofread by Dr. Peter Kazanzides and Dr. Russell H. Taylor. Dr. Kazanzides is a co-founder of the Integrated Surgical System (ISS), a manufacturer of the ROBODOC system, and was the Director of Engineering of ISS. Dr. Taylor designed and prototyped an earlier version of the ROBODOC system for a veterinary orthopedic surgery at the IBM Research in the late 80’s.

Overview of the ROBODOC System

The ROBODOC® system has been developed to increase the accuracy and efficacy of surgical procedures such as cementless Total Hip Replacement (THR) surgery and Total Knee Replacement (TKR) surgery by enabling surgeons to precisely specify the desired prosthesis placement in a preoperative CT scan of the patient and then use the robotic system to accurately machine the bone to achieve that plan.

It began as a joint project between the University of California, Davis and IBM Research. The canine system (alpha prototype) was developed for canine THR in a well-controlled, supervised research environment, i.e., under the active supervision of the developing engineers. It was first clinically used in 1990 for canine patients at a veterinary hospital in Sacramento, California and performed canine surgeries. This alpha prototype went through fundamental changes and improvements to evolve into a beta (investigational) medical device that was operated by surgical teams –- without engineers –- for human clinical trials at multiple clinical sites. The beta version of ROBODOC was the subject of an FDA-authorized, multi-center clinical trial in the United States, and performed over 200 surgeries at a hospital in Frankfurt, Germany. It was then further developed as a commercial-level product to be used in Europe and this required an architectural change from a centralized architecture to a distributed architecture.

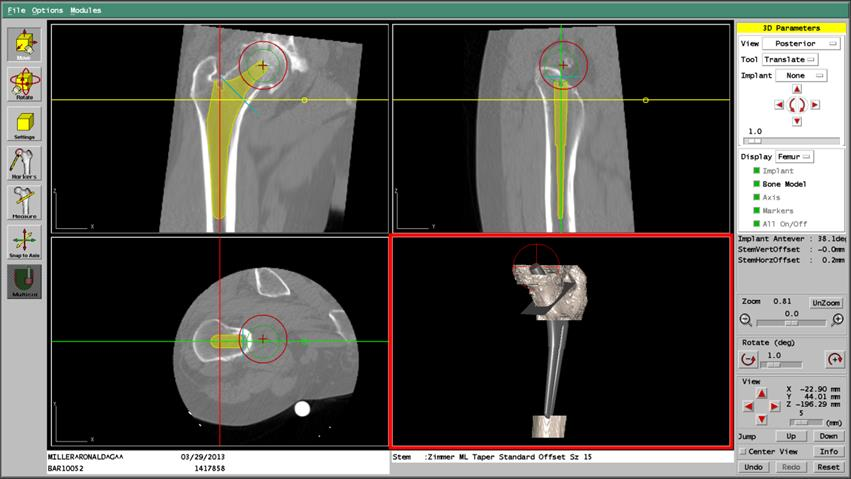

The following figure shows the ROBODOC System. The two main components of the ROBODOC System are the ORTHODOC™ Preoperative Planning System (ORTHODOC) and the ROBODOC Surgical Assistant (ROBODOC). ORTHODOC allows the surgeon to develop a preoperative plan that ROBODOC can execute. The two inputs to ORTHODOC are a Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s femur and a set of implant models based on data from the implant manufacturers. Using implant models and a three-dimensional model of the femur constructed from the CT data, the surgeon visually determines an appropriate implant model with its precise location. Once the plan is finalized, the preoperative plan is recorded and transferred to ROBODOC via a transfer medium (tape or CD).

ROBODOC reads the preoperative plan from the transfer medium and machines a cavity for the implant in the femur according to the plan. To precisely execute the plan, it is required to register the patient’s femur in the preoperative plan with the intraoperative physical reality (i.e., the robot’s workspace coordinates). Calibration of the robot kinematic parameters and the cutting tool’s dimensional parameters also play a vital role in achieving high dimensional accuracy. Based on clinical input, the specification of the robot’s placement accuracy (deviation from the preoperatively planned position) is less than 1.0 mm, and that of the dimensional accuracy (deviation of the machined shape from its ideal dimensions) is less than ±0.4 mm on a cross-section (or ±0.2 mm on each side).

Safety Features of ROBODOC

The principal safety requirements of ROBODOC were defined by a surgeon, who was a user of the system, as follows:

- The robot should never “run away”: No single-mode hardware failure or system error should cause the application software to lose control of the robot motions.

- The robot should never exert excessive force on the patient: Any cutting force substantially more than needed means something may be wrong and the robot better stop its current motion.

- The robot’s cutter should stay within a pre-specified positional envelope relative to the volume being cut: A systematic positional shift in the placement or shape of the hole should be prevented.

- The surgeon must be in charge at all times: The system must provide the surgeon with timely information about its current status and the surgeon must be able to stop motions at any time.

A set of safety features distributed throughout the system were designed to achieve these principle safety requirements. The following presents a partial list of the safety features of ROBODOC based only on the published, academic literature.

- System integrity monitoring (with redundant sensors): The real-time control loop periodically monitors system integrity, such as tolerance checking of primary and redundant encoders at each joint, with the capability to turn off the robot arm.

- Use of state variables for error handling : State variables are defined to represent application-specific procedural flow and are used for error or exception handling.

- Dedicated processor for the safety system : The safety system runs on a separate processor to isolate it from errors in other subsystems and has a direct hardware interface to power othe system.

- Force/torque checks with two thresholds : Force and torque feedback from the force sensor are monitored against two thresholds, PAUSE (1.5 kg-f) and STOP (3.0 kg-f). PAUSE halts all robot motion and turns off the cutter, whereas STOP removes power from both the robot and the cutter.

- Speed limiter (low speed): The low-level software implements the speed limiter. It operates on the output of the trajectory generation functions and limits the robot’s speed and torque. The rationale of this safety feature is that the surgical staff can stop the robot before any hazard occurs if the robot is slow and weak.

- Safety volume (dynamic constraints): During cutting, the software verifies that the cutter tip is within a pre-planned safety volume, with a 3 mm margin for error. The safety volume is derived from the prosthesis geometry, but is independent from the file containing the cutting paths.

- Notification of exceptions to application : Any reflex action initiated by a safety system leads to an exception to the application which interrupts the normal procedural flow and invokes a handler function for error recovery.

- Error detection : Data integrity checks (e.g., if there is any corruption of critical data), data rationality checks (e.g., if case-specific data are reasonable), detection of procedural errors (e.g., if surgeons make procedural errors that can compromise both safety and system performance).

- Startup diagnostics : During start up, all safety- and performance-related components are verified to make sure that they are functioning within specified tolerances.

- User oversight with emergency pause/stop : An external custom pendant with five buttons, including emergency pause and stop, helps surgeons to interact with the system and a graphical display in the operating room provides the current status of the surgical procedure.

References

ROBODOC Literature

This is a list of the academic literature on the ROBODOC System that I have reviewed with focus on its system design and safety features.

- R. H. Taylor, P. Kazanzides, B. Mittelstadt, and H. Paul. Redundant consistency checking in a precise surgical robot. In Proc. of the 12th Annual Intl. Conf. of the IEEE, pages 1933–1935, Nov. 1990.

- R. H. Taylor, H. Paul, P. Kazanzides, B. Mittelstadt, W. Hanson, J. Zuhars, B. Williamson, B. Musits, E. Glassman, and W. Bargar. Taming the bull: Safety in a precise surgical robot. In Intl. Conf. on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), volume 1, pages 865–870, Jun. 1991.

- P. Kazanzides, J. Zuhars, B. Mittelstadt, and R. Taylor. Force sensing and control for a surgical robot. In IEEE Intl. Conf. on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), volume 1, pages 612–617, May 1992.

- P. Kazanzides, J. Zuhars, B. Mittelstadt, B. Williamson, P. Cain, F. Smith, L. Rose, and B. Musits. Architecture of a surgical robot. In IEEE Intl. Conf. on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, volume 2, pages 1624–1629, Oct. 1992.

- B. Mittelstadt, P. Kazanzides, J. Zuhars, P. Cain, and B. Williamson. Robotic surgery: achieving predictable results in an unpredictable environment. In Intl. Conf. on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), volume 11, pages 367–372, 1993.

- P. Cain, P. Kazanzides, J. Zuhars, B. Mittelstadt, and H. Paul. Safety considerations in a surgical robot. In Proc. of 30th Annual Rocky Mountain Bioengineering Symp., volume 29, page 291, Apr. 1993.

- P. Kazanzides, B. Mittelstadt, J. Zuhars, P. Cain, and H. Paul. Surgical and industrial robots: Com- parison and case study. In Proc. of the Intl. Robots and Vision Automation Conf., pages 1019–1026, Detroit, MI, Apr. 1993.

- R. H. Taylor, B. Mittelstadt, H. Paul, W. Hanson, P. Kazanzides, J. Zuhars, B. Williamson, B. Musits, E. Glassman, and W. Bargar. An image-directed robotic system for precise orthopaedic surgery. IEEE Trans. on Robotics and Automation, 10(3):261–275, Jun. 1994.

- P. Kazanzides, B. Mittelstadt, B. Musits, W. Bargar, J. Zuhars, B. Williamson, P. Cain, and E. Carbone. An integrated system for cementless hip replacement. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine, 14(3):307–313, May/Jun. 1995.

- P. Kazanzides, P. W. Cain, and H. A. Wasti. Distributed architecture for a fail-safe robot system. In Proc. of the Signal Processing Applications Conference & Exhibition (DSPx), San Jose, CA, Mar. 1996.

- R. H. Taylor, B. D. Mittelstadt, H. A. Paul, W. Hanson, P. Kazanzides, J. F. Zuhars, B. Williamson, B. L. Musits, E. Glassman, and W. L. Bargar. An Image-Directed Robotic System for Precise Orthopaedic Surgery, chapter 28, pages 379–396. Computer-Integrated Surgery. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1996.

- B. D. Mittelstadt, P. Kazanzides, J. F. Zuhars, B. Williamson, P. Cain, F. Smith, and W. L. Bargar. The Evolution of a Surgical Robot from Prototype to Human Clinical Use, chapter 29, pages 397–407. Computer-Integrated Surgery. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1996.

- P. Kazanzides. Robot Assisted Surgery: The ROBODOC (R) Experience. In Intl. Symp. on Robotics (ISR), volume 30, pages 281–286, Tokyo, Japan, 1999.

Articles on ROBODOC Safety

In case you are interested in further information of the ROBODOC safety design, below are a couple additional articles for reference.

- M. Y. Jung. State-based Safety of Component-based Medical and Surgical Robot Systems. PhD thesis, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, May. 2015.

- M. Y. Jung, R. H. Taylor, and P. Kazanzides. Safety Design View: A conceptual framework for systematic understanding of safety features of medical robot systems. In IEEE Intl. Conf. on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pages 1883–1888, 2014.